Shale in the United States

Last Updated: September 4, 2014

Over the past decade, the combination of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing has provided access to large volumes of oil and natural gas that were previously uneconomic to produce from low permeability geological formations composed of shale, sandstone, and carbonate (e.g., limestone).

Shale is a fine-grained sedimentary rock that forms from the compaction of silt and clay-size mineral particles. Black shale contains organic material that can generate oil and natural gas, and that can also trap the generated oil and natural gas within its pores.

Where are shale gas and oil resources found?

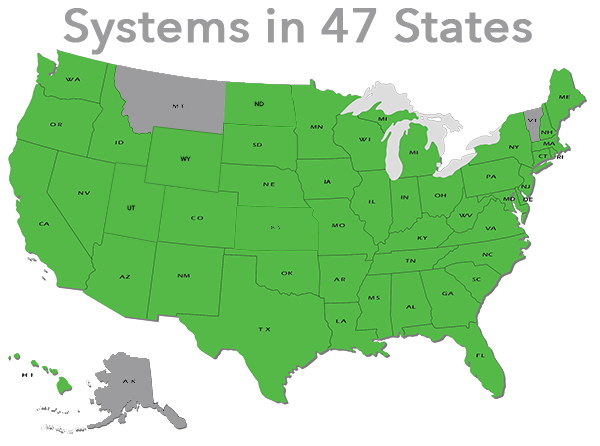

Shale oil and natural gas resources are found in shale formations that contain significant accumulations of natural gas and/or oil. The Barnett Shale in Texas has been producing natural gas for more than a decade. Information gained from developing the Barnett Shale provided the initial technology template for developing other shale plays in the United States. Another important shale gas play is the Marcellus Shale in the eastern United States. While the Barnett and Marcellus formations are well-known shale gas plays in the United States, more than 30 U.S. states overlie shale formations.

Within an individual shale play, geophysicists and geologists identify suitable well locations in areas that have the greatest potential to produce commercial volumes of natural gas and oil. These areas are identified using rock core samples and geophysical and seismic technologies to generate maps of the subsurface hydrocarbon resources in a shale formation.

Shale gas, tight gas, and tight oil

The oil and natural gas industry generally distinguishes between three categories of low-permeability formations:

Shale natural gas

Large-scale natural gas production from shale began around 2000, when shale gas production became a commercial reality in the Barnett Shale located in north-central Texas. The production of Barnett Shale natural gas was pioneered by the Mitchell Energy and Development Corporation. During the 1980s and 1990s, Mitchell Energy experimented with alternative methods of hydraulically fracturing the Barnett Shale. By 2000, the company had developed a hydraulic fracturing technique that produced commercial volumes of shale gas. As the commercial success of the Barnett Shale became apparent, other companies started drilling wells in this formation so that by 2005, the Barnett Shale was producing almost half a trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of natural gas per year. As natural gas producers gained confidence in their ability to profitably produce natural gas in the Barnett Shale, with additional confirmation provided by well results in the Fayetteville Shale in northern Arkansas, producers started developing other shale formations, including the Haynesville in eastern Texas and north Louisiana, the Woodford in Oklahoma, the Eagle Ford in southern Texas, and the Marcellus and Utica shales in northern Appalachia.

Tight natural gas

The identification of tight natural gas as a separate production category began with the passage of the Natural Gas Policy Act of 1978 (NGPA), which established tight natural gas as a separate wellhead natural gas pricing category that was permitted to obtain unregulated market-determined prices. The tight natural gas category was designed to give producers an incentive to produce high-cost natural gas resources when U.S. natural gas resources were believed to be increasingly scarce.

As a result of the NGPA tight natural gas price incentive, these resources have been in production since the early 1980s, primarily from low-permeability sandstones and carbonate formations, with a small production volume coming from eastern Devonian shale. With the full deregulation of wellhead natural gas prices and the repeal of the associated Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) regulations, tight natural gas no longer had a specifically defined meaning, but generically still pertains to natural gas produced from low-permeability sandstone and carbonate reservoirs.

Notable tight natural gas formations include, but are not confined to

Clinton, Medina, and Tuscarora formations in Appalachia Berea sandstone in Michigan Bossier, Cotton Valley, Olmos, Vicksburg, and Wilcox Lobo along the Gulf Coast Granite Wash and Atoka formations in the Midcontinent Canyon formation in the Permian Basin Mesaverde and Niobrara formations in multiple the Rocky Mountain basinsTight oil

In the United States, the oil and natural gas industry typically refers to tight oil production rather than shale oil production. The industry uses the term tight oil production because it is a more encompassing term with respect to the different geologic formations producing oil at any particular well. Tight oil is produced from low-permeability sandstones, carbonates (e.g., limestone), and shale formations. The oil and natural gas industry's colloquial use of the term tight oil is rather recent, and does not have a specific technical, scientific, or geologic definition. The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) has adopted the convention of using the term tight oil to refer to all resources, reserves, and production associated with low-permeability formations that produce oil, including that associated with shale formations.

Notable tight oil formations include, but are not confined to

Bakken and Three Forks formations in the Williston Basin Eagle Ford, Austin Chalk, Buda, and Woodbine formations along the Gulf Coast Spraberry, Wolfcamp, Bone Spring, Delaware, Glorieta, and Yeso formations in the Permian Basin Niobrara formation, although located in multiple Rocky Mountain basins, is primarily producing oil in the Denver-Julesburg Basin

Does the United States have abundant shale resources?

Yes, the United States has access to significant shale resources. In the Annual Energy Outlook 2014, EIA estimated that the United States has approximately 610 Tcf of technically recoverable shale natural gas resources and 59 billion barrels of technically recoverable tight oil resources. As a result, the United States is ranked second globally after Russia in shale oil resources and is ranked fourth globally after China, Argentina and Algeria in shale natural gas resources.